Could you tell us something about yourself?

As far as I know, I’m the world’s only Finnish globally active professional perfumer. I grew up in Helsinki and attended Finnish-Russian language school for 12 years. By 18, I was fluent in three languages (Finnish, Russian and English) and somewhat able to use French and Swedish. I was a total bookworm and grew up on old school science fiction and Russian classics. I had also been writing for publication since the age of 9 – so languages seemed to make sense as a career choice. I was going to be an interpreter and I even enrolled on a degree course towards that path, but a gap year turned into a big change - and here I still am, in the UK. I’ve forgotten my Russian now; I’d have to live there for a year or so and it would come flooding back.

I have a 9-month-old Finnish Lapphund called Taisto and I’m married to a Brit with Finnish and Northern Irish heritage. We live in Leighton Buzzard.

It’s easy to look back and think you see a pattern where there wasn’t one, but it did take me a while to realise that not everyone necessarily catalogues their memories with the odours first, memory second. Smelling everything and remembering the exact odours was second nature to me long before I even knew what a perfumer was.

How did you become a perfumer? Did you go to a perfume school?

My route to perfumery is unconventional and filled with side quests. It’s also a bit like When Harry Met Sally, in that perfume was a huge part of my life all along but I didn’t consider it as my one true love until I was in my 30s. The best summary is that while I didn’t attend ISIPCA or an internal perfumery school in a big fragrance house, I have assembled the equivalent of a formal perfumery education from learning on-the-job, academic study, mentorship, and self-study over a period of 12 years. I think the biggest acceleration in my learning came from starting the business with Nick – I was able to get the kind of help that would normally only be available to corporate perfumers. Learning perfumery and becoming more than just competent at it takes more than one human lifetime’s worth of work, so it’s good to have help.

I worked part time after school from age 13 to 20 for a superstore (the kind that stocks everything you can think of and also has distinct departments like cosmetics & fragrance). Over the years I gained a solid foundation of product knowledge in all the brands they stocked. I had also built what nowadays is called a “perfume wardrobe” (and back then in the 80s was considered excessive) – I had a minimum of 20 perfumes in rotation at any one time. Balahe by Leonard, Givenchy III, Paris YSL, Femme Rochas and Fendi were some of my favourites from that time. In the 90s, I wore a lot of Coco. It was my clubbing perfume.

I had always secretly wanted to be an artist, but an unsuccessful art school application in Finland left me thinking I needed to be pragmatic, so I enrolled in London College of Fashion. I graduated in 1996 and went on to work in film, TV, fashion, and theatre as a make-up artist and hair stylist. Our curriculum included cosmetic science and that was my first experience of product formulation. My dream career at the time would have been to work for Jim Henson’s creature workshop – but I had no idea how to achieve that goal.

Instead, I ended up backstage in theatre and fashion shows; magazine shoots and musicals; on a HBO film set in Hollywood creating 1930s hair styles, and creating body painting designs for a fantasy film that was really a thinly disguised soft porn film.

As much as that was fun and exciting, I started to crave some stability. My income had to be supplemented by continuing to work in – guess what? Cosmetics and fragrance. The scheduling of work on set often clashed with my shifts at London department stores (I worked in every single one of them during this time) and sometimes I ended up doing ridiculous workdays that involved an 8-hour shift at Dickins & Jones, then dashing to a theatre to get the actors ready – and finishing at 1am.

I got a job as a regional training manager for a UK cosmetics and fragrance distributor. Their main focus was fragrance, and this was the first time I saw what had been right in front of my nose all along. I started looking into who creates fragrances, where the materials come from and how the industry is set up. All of this was still fiendishly obscure, so it was not easy. The internet was in its infancy and there were no helpful websites like Basenotes and Fragrantica, nor any guidebooks like those edited by NEZ. What I would have given for a place like the Institute of Art and Olfaction back then! The inner workings of actual perfumery seemed like an impenetrable wall.

In the end, I found my way to a cosmetics company that was both known for its fragrances and – crucially - created all its own formulas, including the fragrances, in-house. I had to start from the shop floor and work my way up, but I became a junior perfumer there, through training and participating in all the fragrance activities (buying trips to see raw materials; learning how to quality control; even learning how to compound in bulk on the factory floor – that was such an eye-opener as they were doing everything by hand; your 2% of vanillin in a formula looks really intimidating when it’s a mound of powder you have to solubilise). I also helped train their in-store training team and participated in the launch of their own quirky perfume brand, which involved travelling around the world with their perfume gallery concept. Fell in love with Seoul, New York, and Tokyo.

The products that I worked on as a perfumer were varied, and the raw material palette was a mixture of expensive naturals and basic synthetics. I compounded all my own formulas and trials of course; there were no assistants. This was also very useful training. They funded my study on the ICATS Diploma in Aroma Trades course, on which I won the David Williams prize for best student in my first year.

I moved on after 7 years there, to a small family-run ingredient and fragrance supplier. My role was 80% technical management (fancy term for all incoming and outgoing quality control, plus all regulatory) and 20% perfumery. It was a crash course in the inner workings of the supply side and really educational in many ways; for example, I learned how to properly assess and analyse raw materials and how to detect minute differences in qualities by nose alone. Perfumery was completely different there – very cost conscious, focused on synthetic materials and on functional fragrances. But I did do my first candle fragrances there and realised I enjoyed that medium.

After that, I worked for a colleague from the British Society of Perfumers where I had been a council member for a few years by then; she needed lots of help with the regulatory consultancy and training side of her business and as a reward I also got to help her create fine fragrance accords and keep the lab organised.

Above, clockwise: Olfiction office, Nick Gilbert/Pia Long, Thomas Dunckley, Ezra-Lloyd Jackson/Pia Long/Marianne Martin

Can you tell us more about Olfiction?

One serendipitous bit of timing led to my good friend and sought-after fragrance expert Nick Gilbert becoming available exactly as I was starting to get frustrated at not having enough perfumery to do – and we had a boozy discussion at my dining table about “starting a business one day.”

Three months later, we had a business and our first big account. This was in 2016. We started the business with no outside funding and that’s how things remain to this day; Nick and I co-own it outright.

In the beginning, it was just the two of us, and our business was founded on a combination of our skills and dream projects: olfaction and fiction. Perfumery and storytelling. We shared these twin passions and had experience in both. Two years in, we needed to expand the team and Ezra-Lloyd Jackson joined as a lab assistant, and another good friend Thomas Dunckley (aka The Candy Perfume Boy, six-time Jasmine award winning fragrance writer) started helping us part-time with the storytelling and training side of the business. Soon after that, Marianne Martin, an experienced chemist, perfumer, and perfumery tutor at the London College of Fashion approached me to help her edit the perfumery module for the course she runs – through that collaboration, we clicked and enjoyed working together so much that she joined our team as an independent consultant. She has been instrumental in helping to train Ezra who wants to become a perfumer. One of the best things about our perfumery team is when we get together to smell materials and end up with three perspectives from three generations and backgrounds. It’s so inspiring that I still get goosebumps!

I knew right from the start of Olfiction that this was my opportunity to finally become a full-time perfumer and I did not want to add the bulk compounding, regulatory or filling to our business straight away. It also seemed too much to expect for us to immediately source and stock all the raw materials I wanted. Nick agreed. So, we knew we needed a partner and that’s when Nick suggested we should ask Accords & Parfums, as he had an existing relationship with them through his previous work for L’Artisan Parfumeur and Penhaligon’s.

Above: Garden of Accords et Parfums

Accords & Parfums was founded in 2004 as an extension of Edmond Roudnitska’s Art et Parfums, and they are almost like a publishing house for independent perfumers. They are based on the Roudnitska estate in Cabris, just outside of Grasse. We have an exclusive agreement as the only ones in the UK working through them. It’s such a privilege and it has helped us so much. They source and stock thousands of materials and we can have any we could ever want; currently our lab has around 400. They provide access to formulating software which allows me to do the precise work of the endless calculations required in formulating, reformulating and regulations. They provide stability and safety testing and use the same standard of quality control and precise robotics for manufacturing as the bigger houses. It’s an ideal situation.

Who are your clients? What are some of the perfumes and candles you have created? Which scents/candles you have created so far are special to you?

On the perfumery side: niche & luxury brands, hotels, home fragrance manufacturers (and sometimes unexpected businesses who wish to use perfume in PR or marketing) – on the storytelling and consultancy side: well-known luxury fragrance brands, fragrance industry organisations, larger fragrance houses, distributors and retailers. We also do one off events sometimes, for example with theatres, and provide education for some university courses that include formulation science or marketing. Ezra has been scenting music gigs and giving smell training and perfume making workshops for children. Our aim is to be a positive, enthusiastic force in the world for perfume and smells, and to get to do cool stuff. So far, we’re heading in the right direction.

One of the frustrating aspects of this trade is that there are still many projects under NDA, and also many that take a long time from the very first idea to the final product on the shelf; sometimes years. More and more now, we’ve been named as the perfumers or providers for even some of our bigger projects (like the Mach-Eau we just did for Ford). But this is still the exception.

My favourite smells are quite a contradiction – on one hand I love bright, dewy green scents (and I got to really explore that style in the recent collection I did for Designers Guild as well as in the Succulent candle for our own brand Boujee Bougies), and on the other hand, I love leather aromas so much it’s bordering on a fetish, so of course I had such a good time creating Terror & Magnificence for Beaufort and the Cuir Culture leather candle for Boujee Bougies. In the last few years, I’ve also created for Ghost, Mercedes Benz and Browns Fashion.

The pace of launches slowed right down in the last two years (and we all sadly know why), but conversely, this means there are so many to come in the next 18 months that it seems a bit silly! The first of the “next” list of launches just happened; two candle fragrances for La Montaña (Mistela and August Sunset), and in 2022, Boujee Bougies will see the launch of two new candle fragrances and four perfumes.

Of the recent work, I have adored working on Chipmunk (am I allowed to say that here? It’s true!) because I was able to draw on so many vivid scent memories and add such a twinkle in the eye of that perfume as well.

There are also two perfumes coming out in 2022 that are special to me. I created each with two separate friends in mind; I can’t wait for those to become real. One of those is part of a collection of seven perfumes for a new luxury niche brand, founded by a Mayfair jeweller.

How do you describe your perfumery style? What and who inspire you? What are some of your favourite perfumes?

Magic realism is the best way I can describe my signature style. I first aim for hyper-realism, then twist it. I often add little in-jokes or Easter eggs to the creations, regardless of the medium. Either word play or something to do with the concept itself. Of course sometimes the inspiration is completely abstract, and that’s when the instinctive feel for cross-modal interpretation is useful. Thinking in textures, colours, emotions, states of mind and translating those into scent, or vice versa. I also love decoding what the client really wants, although Nick is our main client contact and helps a lot with this process.

In a way, I did end up being an interpreter – an interpreter of another person’s imagination into scent.

Inspiration is absolutely everywhere, and always links seemingly disparate concepts or materials in that daisy chain of “what if” that all perfumers are probably familiar with – perfumery to me is a state of mind, a constant way of being, experiencing the world, the sensory input and the sensory imagination and memories in your own head as a continuous sea of inspiration. All I need is a command “think of this idea”, either internally or externally, and the cogs begin to turn, pulling inspiration from materials I may have thought I knew but now want to re-smell through the lens of this new idea, or an evening walk in nature, or the green tea I am sipping; a vegetable I’m chopping for dinner… art I see in a book. Everything. Everything is inspiring. If I have been working too much on output and creations, I sometimes deliberately stop to visit an art gallery or gardens or a forest, just to recharge the creative mind with new input. I am always reading (multiple books in progress at all times), and a lot of thoughts come from there, too.

Favourite perfumes are split into two types – the ones that I can wear without thinking about them (Annick Goutal Mandragore, Le Galion Eau Noble, Guerlain Cuir Beluga) and perfumes which to me are either linked to a special memory or just so beautiful in themselves that I need them in my collection even if I don’t get to wear them often – too numerous to list, but for example Ambre Sultan Serge Lutens, Mitsouko Guerlain, L’Artisan Dzongkha.

Let’s talk about Chipmunk! How would you describe Chipmunk? What are some of the ideas and inspirations behind this perfume?

The timing of this was so good. I had just received a sample of a material I hadn’t used before, oak barrel absolute, and I had gone on to create a smell-alike accord to study the olfactive qualities. I had also started working on a hazelnut accord – more like fresh, just shelled, not exactly fully gourmand. I constantly do little studies like this because I am curious. And exactly then, our talks about a Zoologist perfume landed on the Chipmunk and I got very excited.

The oak is the central trunk that I pinned everything else on in the perfume, and the hazelnuts are mixed with acorns, seeds and leaves inside the burrow. All the forests I’d ever visited came to whisper their stories to me and I almost felt like I was creating a scent for a Ghibli film, being the perfumer-Totoro, willing for things to sprout and grow into tall, towering trees through scent. I remembered the smell of still sticky tree sap from conifers from my childhood, and the resins in the perfume echo this.

Did you build it with different accords? How complex is this fragrance? What are some of the naturals used? Are they specials and your favourites?

With fine fragrance, perfume – I tend to work quite methodically. Starting with little accords of individual effects, then blending them in different proportions (even though at this stage they’ll be “messy”, I know what I’m looking for – the unique voice of the perfume). Once I know what to do, I explode the whole formula, tidy it up, do it again, and start to edit, edit, edit.

The key accords that I started with were the realistic oak warmed in the autumn sun, the forest floor and burrow, and the fresh hazelnut. For the burrow, I used an aromachemical called Terranol (a Symrise material that has aspects of fir balsam, moss and patchouli, and I think of it as luxury geosmin; more earthy, less beetroot). As I used natural fir balsam and patchouli, too, they formed a beautiful bond.

The camomile was a whimsical but useful addition - it sweetens the composition without becoming gourmand, it adds earthy notes without dirt, and it adds herbal floralcy without being overtly flowery. Plus, I enjoyed imagining her in a clearing in the forest, nibbling on a flower.

For the magic part of the magic realism, I used expensive, fuzzy synthetic musk for her fur, and added some fantasy woody materials as well as the naturals, for example Javanol which is just lovely. It added a kind of smoothness to the naturals.

There are a couple of hidden qualities that are a nod to her habitat and geographic location; I want people to discover them by themselves rather than to reveal all here.

Do you think Chipmunk is more for women, or is it unisex?

Perfume has no gender in itself – so, the end result can be worn by everyone. Of course, this concept was based on the girl scout chipmunk, so I wanted that combination of hyper-realistic nature and fun artistic interpretation of her to come across. This perfume has cute and fluffy elements and I wanted it to be a scent that should bring childlike joy and a sense of calm to the wearer. I suppose those can be feminine qualities. So, it’s a feminine-leaning creation that can be for anyone who wants to wear it. Having said that, because our individual odour perception is so based on our own receptors, memories, and context, for some people this could read as a masculine because of all the woody aspects and the animalic base notes.

What are some of the projects you are working on? Can you share them with us?

I am currently creating perfumes for a chain of barbershops, working on an oil-based perfume for a potential new offshoot of an existing project, creating a few dozen candle fragrances for various clients and preparing the Boujee perfumes for the stability and safety testing part of the process.

Hi Cristiano, could you tell us about yourself?

Hello everybody. My name is Cristiano Canali. I was born in Italy, and I work in the perfumery industry.

You have a Masters degree in Pharmacy, and I imagine it required a lot of hard work and dedication to achieve that academic level. But now you are a perfumer. When did you have a change of mind? Did you find foregoing all the effort and years of study a big struggle and still worth it?

The high schools in Italy do not challenge you to choose the path needed to achieve the job you dream of. Most likely you find yourself after the diploma still building a plan. Following my family heritage and being gifted with scientific subjects, medical studies were the logical way for me. I chose pharmacy, like my grandfather did. The five years of university went well, and I discussed Ayurvedic products (the traditional Hindu system of medicine) in my final thesis, since I have been always attracted by plants’ properties. Thanks to those studies, during a trip to the south of India, I got in contact with some local producers of sandalwood oil who were supplying the perfumery industry. This initiated my curiosity in the art and science behind the scents. This is how, after some years of work, I decided to attend the prestigious ISIPCA school in Versailles to perfect my preparation and push me into the fragrant world of perfumery.

You once told me that you were ‘old’ when you started your perfumery career. I thought that was ridiculous. But why did you think that? Have you changed your perception since then?

More than old – I was already experienced and exposed to working habits, so it was challenging to get back to school, restart from scratch and leave behind a secure career and life. But the urge to express myself was too strong. Also, the connections between pharmacy and perfumery are many: both utilize formulas to find ideal solutions. Chemistry and botanical ingredients are my daily bread. Both involve glassware, pipettes, and balances to produce and fabricate; clients and their satisfaction are key in order to deliver the expected product; and, last but not least, developed sales skills are required in order to be successful. As you can see, there are many parallels. Overall, pharmacy taught me how to cure the body. Perfumery is teaching me how to heal the soul.

You are now working at Argeville. Could you tell us a little about the company and your work there? What is your goal as a perfumer?

It’s been one year since I joined Argeville, a leading company in the south of France. The region is well known for its moderate climate all year, for its beautiful nature all around, and as the womb and historical center of the perfumery industry. Argeville is a dynamic company founded in 1921 and owned since the '80s by the same family. It has a clear goal of global excellence, and to offer solutions in fragrances, flavors, and a well-esteemed natural extracts palette to a wide portfolio of clients. We have different facilities around the globe and a pool of talented individuals that together form the strength of this company. My daily job is to understand clients’ needs and translate them into fragrances, both in a creative and technical way. Our evaluation team supports perfumers to achieve these tasks and is the link between creatives and the sales team that interacts with the clients and deals with the commercial strategy. My goal is to evolve in my role as perfumer, diversify my efforts by becoming more prolific, intensify my presence in the market and, more than everything, bring new creative challenges to a wider pool of aficionados. I love my job because I learn and improve on a daily basis.

Zoologist Bee is the fourth officially credited perfume designed by you. That might not be a lot, but on the Internet I have encountered much praise from fans of your work who say they love your work and style. Are you aware of your own style? Can you describe it?

I take every opportunity to explore synergies and contrasts between ingredients and work them into new olfactive ideas. My creative drive comes from nature itself, which already offers all the answers in a minimalistic complexity. It's for us to just grasp the meaning. I like to invest time in the briefing proposed, to know the designers better, smelling their actual line, and understanding where they want to go. I focus my attention on perceptions and intuitions, silage and intimacy, simplification and faceting. Another benefit comes from supporting Osmotheque, the only museum of liquid perfumes in the world, where I have been exposed to iconic fragrances and forgotten gems of the past that allow me to understand the archetypes and the most unconventional creations in history. On top of that, I am not afraid stepping out from the actual market trends that I constantly analyze. I try to seduce the most exigent noses with unconventional fragrances and satisfy consumers’ expectations. Still, I think it is early to talk about a personal signature: it is more a graphism, or a beginning of calligraphy.

What are some of your favorite perfumes and why? Do you have a favorite perfumer(s)?

Having spent many years working in Paris, where the pulsating heart of the industry beats, I had the privilege to get in contact with the greatest masters as a daily source of knowledge. From them I have learned different creative approaches, aesthetics and signatures. There is no doubt that thanks to them I kept my motivation and passion high during those years. I have great regard for Carlos Benaim, Dominique Ropion, Anne Flipo, Sophie Labe, Bruno Jovanovich, Christopher Sheldrake, Olivier Cresp, Alberto Morillas, Sonia Constant, Marie Salamagne, Pierre Bouron, Michel Almairac, Jerome Epinette, Jean-Louis Sieuzac, Fabrice Pellegrin, Aurelian Guichard, Daniela Andrier, Alienor Massenet, Veronique Nyberg, Nicolas Beaulieu, Julien Rasquinet and some others. Those people are shaping the market and driving us into a new age of perfumery.

My overall most-appreciated fragrances include: Aprée l'Ondee by Guerlain; Tabac Blond by Caron; Femme by Rochas; Opium by YSL; Fumerie Turque by Serge Lutens; and Une Fleur de Cassie by Frederic Malle.

I remember after you showed interest in designing a scent for Zoologist, we spent some time deciding which animal to base the perfume on. Your first suggestion was “Toad”, which I thought was not a very marketable perfume title…

It was a fun process to think of the animal you find the deepest connection with. Out of the various options, my attention was captured by toad. I find them cute, with those big eyes, their funny way to move on land, and their long hibernation time during winters; with their permeable skin, they are an index of environmental status, and when they are in groups they create great symphonies during the summertime. Also, they might have magical powers and hide a prince behind their uncertain look.

Later, I asked you what your favorite perfumery ingredients were, and one of them was beeswax. I thought that was something Zoologist had not explored yet.

Among my favorite natural ingredients, sandalwood has a special place for me: it is a fragrance itself and is my personal link between pharmacy and perfumer. I like to work with floral notes like magnolia, cassie, orange blossoms, tuberose, jasmine and violet for the complexity and sensuality they bring in composition, no matter the gender. I also have a predilection for animal derivates such as castoreum, civet, ambergris and beeswax for their unique odor profile and warmth, even in small traces. Beeswax is uncommonly overdosed in modern fragrances.

Do you know how beeswax is collected and processed as a perfumery ingredient?

The process of harvesting the waxes from beehives is more a ritual than an industrial production. Availability is very low, and not all the companies are capable of processing this royal ingredient. I am lucky it is one of the specialties in the Argeville compendium, and our Director of Ingredients has a special affection to it, being a beekeeper himself.

The process starts with selecting the best apiculturists. We have special partnerships here in France. Then the honey is extruded by centrifuge from the frame during a period in which the bee larvae are not in their hexagon cages. The wax is then treated under solvent extraction to obtain a golden butter, lately purified with ethanol to obtain the precious absolute. The smell is warm, opulent, waxy with flowery notes and tobacco / hay undertones. It is difficult to classify it in one single family, since it has so many facets: gourmand, balsamic, spicy, flowery, nutty, leathery, fruity... pure magic.

I suggested to you that it would be fascinating if Bee could take the wearer on an olfaction journey from a bee’s perspective – from leaving the claustrophobic beehive, to collecting nectar from flowers, and returning to the hive to deposit the goods. Do you think you have succeeded with Bee?

Bees themselves are amazing: they are so efficient, they fly all over, unstoppably searching, they delicately bathe in the flowers, providing pollination and hybridization, and magically they know how to go back to their hive to produce the honey and work as a collective to proliferate and survive in service of their queen. She was my inspiration. Once awakened, somehow she is selected among the others’ larvae. The noise is buzzy, light is low, temperature high; she is fed with royal jelly to promote abnormal growth and miraculous health; once ready to leave the small cell, she is constantly followed and supported by her sisters exploring her castle; after some time she is ready for flight and to explore her flowery and infinite kingdom, ready to start a new colony with a bunch of devoted followers. I find all of this poetic, charming, and nostalgic.

Could you tell us some of the ingredients that you have chosen, and their effects in the perfume? What is the “royal jelly accord” in Bee?

The royal jelly accord is the core of the fragrance. It has been the natural choice as the key ingredient to start developing the fragrance. Beeswax is the main component. This accord is perceivable vertically in the composition, to recreate this disorienting sound of wings flapping reverberating within the comb. I used in top notes an orange concentrated, an in-house specialty that captures the very essence of sweet orange. Also, a ginger syrup accord completes this fizzy citrus short opening. Of course, we wanted to adorn these magical ingredients with the most honey-dripping flowers like broom, an endemic bush typical from Italy, orange blossoms with their inebriating smell, and some other pollen-rich flowers such as Mimosa from France and Heliotrope. The bottom notes go into a comforting musky powdery atmosphere somehow, like when a bee flies over multicolored meadows: sandalwood brings creaminess and texture, benzoin kicks in a subtle smokey note that contrasts with the tenderness of vanilla, and labdanum gives this final warmth.

Many people have wondered if real honey is used in Zoologist Bee. Can real honey be used in a perfume? Why not? And what did you use to create the virtual smell of honey?

Personally, I have never smelled a perfumery-grade honey derivate, but I am sure you can find some small productions. Honey itself exists in so many different qualities like chestnut, acacia, lavender, rosemary, eucalyptus, pine, and others that it would be too much of a restriction. Sincerely, I was not really interested in using this ingredient, but more in recreating an atmosphere that could embrace the circle of life of those incomparable drones. Enchanting this kaleidoscopic beeswax absolute with some of the most precious flower extracts, we recreated a honey atmosphere without being overly sweet or sticky, overly flowery or waxy, but finding a harmony among all these qualities.

What is next for you? Do you want to create another scent for Zoologist? If so, what kind of scent would that be?

I am very glad I had the possibility to work with Zoologist and you Victor. For sure I would love to extend our collaboration, if there might be the occasion. Bee is a very direct and figurative-realistic fragrance, so in the future I would prefer to interpret a more conceptual animal, one that is dominating his environment and has been in the symbology of human legend since the dawn of time.

Hi Celine, could you tell us about yourself?

I grew up in Grasse, France in the ’80s, when the heart of the city was still beating thanks to the fragrance industry and the entire city’s smell varied according to the distillation of raw materials for seasonal arrivals. No one in my family was related to this industry, and I didn’t go to ISIPCA (perfumery school). Still, as a child, I wanted to be part of this industry one day – on the brand side, though, because in the ’80s and ’90s the ad campaigns and launch events were stupendous! Therefore, I went to business school and interned at Chanel, Dior, Vuitton and Mane, where I discovered the “backstage” world of perfume creation. I LOVED it. From that moment on, my goal was to gain the olfactive knowledge I needed to become a perfumer.

How long have you been a perfumer? Did you always aspired to become one? What is your favourite perfume?

I have been a perfumer, including my time at IFF perfumery school, for 17 years. As a child, I had high interest in perfumes. My nanny’s husband worked in the Roure factory, and when he came back home his clothes were impregnated with the aromas of raw materials. I collected fragrance bottles, really digging for the rare ones, and my grandfather (who loved gardening) used to tell me: “A garden, you have to smell it, look at it, taste it, touch it and hear it.” So I received an education in nature’s beauty and resources. Plus, all the women in my family were either very sophisticated and loved rich perfumes that would leave a huge sillage, or adventurers who would bring back exotic olfactive treasures they’d found in some remote place. That’s why I have a taste for decadent, opulent, and sensual fragrances, mostly in the oriental or amber family. Otherwise, I like big white florals. Alas, my all-time favorite, Versace Blonde, has been discontinued.

How did you become a perfumer at IFF?

It was really after my internship at Mane that I suddenly put all my effort into getting olfactive training to become a perfumer. It was with this mindset that I joined IFF in Milan, Italy, where I studied for two years after work hours, smelling and classifying raw materials and market products with someone who trained at Roure’s school back in the day. I then passed the internal competition to enter the newly re-opened IFF perfumery school program, where I was trained at IFF creative centers in the Netherlands, New York, Paris, and Grasse. So my background is kind of unusual for a perfumer. I’m grateful to IFF for being attracted to an unorthodox profile like mine.

IFF is one of the most renowned big aroma chemical companies in the world. It hires a lot of people, but do they have a lot of perfumers? Is it hard to become an IFF perfumer? What does it take to become one? Do they train and hire new perfumers every year?

At IFF, we have worldwide around 120 creative perfumers across categories, including around 30 in fine fragrances.

Fun fact: there are actually fewer perfumers in the world than Nobel Prize winners!

It is very hard to become a perfumer, first because the opportunities for being trained are very slim. Then there is a lot of competition, and not everyone trained will become a perfumer. It is a very long and slow craft to learn. One needs to have not only artistic talent, but also a strong psychological mindset. About 95% of what we do goes into the garbage, and we interact with people all day long whose job is to criticize our creations.

Hence resilience, patience, combativeness, and being a good listener are key qualities to have, as well as an indestructible faith in yourself and your work. IFF is constantly training a pipeline of young perfumers according to the category and geographical needs of the company. It’s also partnering with ISIPCA on a special program. Each year, some are hired by IFF.

Can you describe a typical day for an IFF perfumer? How many different work-in-progress perfumes do you juggle each day? What is the average number of revisions it takes to finish a perfume?

I usually like to start my day composing new formulae. I let the freshly compounded reworks sit for at least half a day (in the case of rush projects, we usually don’t have much time!). I am very productive in the morning and don’t like to be disturbed. I am always excited to smell my work with evaluators. The most exciting part is when we put the best reworks on skin and pick one or two to present to the brand. During my day I interact mostly with my lab assistant and evaluators, with sales to prepare strategy, with marketing to work on concepts and olfactive stories, and with people responsible for toxicology and consumer insight. One of my other favorite times during the day is when we meet with the brands to present our work. That’s when all the detailed work done backstage takes on life in the proper context. There is constantly this dual dialogue: internal and external. When one of them is missing, it shows in the final product. It’s like something is not aligned.

At IFF, perfumers have to juggle many projects, covering the whole range of the olfactive offerings out there: from specialty to masstige, from prestige to niche. Perfumers need to be agile to work on different segments. Sometimes one perfumer is working on several olfactive propositions for the same project.

There is nothing like an average number of revisions. Each project is different. It may take up to several hundred of revisions to create a blockbuster that will be tested in different markets, with often several perfumers collaborating on the same olfactive direction. This is not the case for less-complex projects. Usually, when a perfumer truly invents an idea that is not inspired from something that already exists, it can take several years of work to develop an edgy accord into a finished product. When I read reviews, it makes me laugh when people think that mainstream projects are easier to win. It is completely the opposite! Because the perfumer usually has to start with a strong and innovative accord with a great story, and then – and this is the difficulty – she or he has to transform it into a well-liked complex fragrance that is highly adopted in worldwide markets known to have very different olfactive preferences.

Above: Celine Barel at Perfumarie New York. Credit: Perfumarie Instagram

To my knowledge, in the perfume industry it is not common to credit the perfumer. Fragrantica’s database lists about 15 fragrances designed by you. That seems to be a small number. Is it safe to guess you have designed many more, but they are not credited? What are your thoughts on that? What are some of the more special perfumes designed by you?

It’s true. A few years ago, it was not a widely adopted trend to name the perfumer, especially if they were younger. Today, some brands still do not want to credit the perfumers, and we oblige them. Among others, I have created for Jo Malone, Tory Burch, Calvin Klein, Hugo Boss, Lancome, Loewe, Oscar de la Renta, Aramis, Dunhill, and Jil Sander.

Lately, thanks to the niche world, with Frederic Malle being the innovator in the matter, perfumers, like designers in fashion, have started to become an acknowledged asset to promote the universe of a fragrance. This has helped to bring back the “art of perfumery”, with this underlying idea there is true craftsmanship and a visible creator behind a perfume creation.

The fragrance industry has changed a lot over the past few decades. There are now many niche perfume brands and self-taught perfumers creating their own indie perfumes. Do you think a professionally trained perfumer has significant advantages and knowledge in terms of perfume composition? On the other hand, do you think indie perfumers are more likely to create more unique, creative or bold scents because they are not bounded by vigorous training?

The fragrance industry has suffered for many years because of the absence of a clear definition of what a “perfumer-creator” is. Therefore, a few years ago, the French Society of Perfumers took the initiative to establish a strict code of what officially defines the skills and competencies of a perfumer-creator.

Receiving academic training has never stopped anyone from breaking the rules, innovating, or being bold. Quite the opposite. It is easy to shock and draw public attention when you pile up odours or/and overdose them through a lack of knowledge; it is another one to translate a vision, an intention, through a composition and find a new “disturbing harmony” where the shock is right, the balance is right.

The ability to create fragrances that are considered unique, creative or bold comes from two main conditions: first, the absence of olfactive tests; second, the opportunity to work directly with the brand founder or artistic director, which allows you to collaborate with the person in full charge of the brand’s vision. Usually that person is a risk-taker who is passionate about fragrance and eager to innovate. Last but not least, we usually work in a niche with a much higher price point and with no filtering layers to please at different stages, whose individual tastes may not be always aligned.

So, independently of being created by professionally trained or self-taught perfumers, the niche/indie market has done an amazing job at reinvigorating the whole world perfumery market in all its segments.

This “renaissance” is due to “riskier” fragrances driven by stronger olfactive statements, ones that are more creative and often more qualitative in terms of raw materials, have great marketing stories and /or packaging, and more selective distribution. Nowadays, people do not want to smell like everybody else, especially the younger generation. They’d rather stay away from the “best testers” to explore more scents off the beaten track.

Let’s talk about the perfume, Squid, shall we?

The collaboration between Zoologist and IFF was perhaps very serendipitous. About a year ago (2018) a perfume shop opened in New York and Zoologist was one of the brands that they carried. Since IFF has an office in New York, they discovered Zoologist when they visited the store. Subsequently, the management of IFF New York contacted me to ask if I was interested in a collaboration. To be honest, I was shocked, because I thought big aromachemcial companies like IFF were only interested in big perfume houses that sell millions of bottles. Of course, I didn’t want to pass up the opportunity, for I had always wondered what it was like to have a perfume designed by “the big one”. The very kind client manager (who was the middle person between me and the perfumers) asked me for some concepts for a perfume that I wanted to make. I gave her three. Those three fragrances were all very challenging to design, and the briefs had been sitting on my computer for a few years. A week later she told me that all of them had been snatched up by three different perfumers! I expected that only one perfume would be chosen. She also told me the names of the three perfumers and who would be designing which animal, and you were doing Squid.

Now, I have to ask, how does a client’s brief usually funnel down to a perfumer? Is it common that a perfumer gets to choose which perfume she wants to design, or does management make the choice?

Regarding high-stakes briefs, there’s a strategy from management to have this or that perfumer work on it. Clients can also request specific perfumers to work on their creations.

As far as Niche’s briefs are concerned, the perfumer’s desire to work on it is key. The customer-perfumer relationship is crucial and usually must be much tighter in order to create a strong olfactive statement.

In my case, I loved your brand. I loved how the animals were portrayed. It speaks to my “Peter Pan” side, a fantasy world where animals are true characters and have an olfactive identity. It reminds me of the Victorian age, one of my favorite historical periods.

And why did you choose Squid?

I absolutely wanted to work on Squid. Some people were saying to me, “Squid? Yuk! No one wants to smell like a fish market!” I cannot understand how people can get so literal!

Immediately, in my mind I was in Jules Verne’s A Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, with a frightening giant squid coming from the deepest part of the ocean. It took me to Japan or China, as supposedly the giant squids live in those waters, so I knew there should be some incense in the accord. Squid bone is the starting point for ambergris: the sperm whale produces a fatty substance to wrap the bone. And coincidently, maybe a month before receiving the Squid brief, while I was swimming in Nikki Beach in Dubai, I hurt my foot walking on a huge squid bone. I smelled it, and it was beautiful, more pungent, sweet and grainy, like Tonka, very salty and rawer than ambergris. I brought the squid bone back and we did a headspace analysis on it.

Therefore, Squid is really based on three pillars: the Living Squid Bone (or headspace) accord in the dry down, the solar saltiness (an airy, salty, ethereal floral impression) in the heart, and mystical frankincense on top. Then you asked me to emphasize the melancholic and inky feeling, as well as the spicy intro. It brought me back again to Jules Verne, who wrote at the height of Romanticism. So I envisioned an olfactive impression that would translate at the same time a calm and stormy mind, going from a deep dark mood to a bright happy place. I was listening to Beethoven a lot to put me in this Romantic mood. And we did it!

I’d also imagined that no one would like to smell like a fish market or a fishy squid. So how did you tackle this project – a perfume named Squid – to make it representative but also wearable?

When I create a fragrance, I always keep in mind that no matter how creative the initial concept is, in the end it will be worn by a person who needs to feel confident about wearing it. A fragrance is like a suit or a dress: it can be creative and edgy, but no one wants to feel uncomfortable wearing it.

Smells have been through centuries, cultures, classes. They are a powerful social marker. It is a matter of being accepted or rejected. Tell me which fragrance you wear, and I’ll tell you which social group you belong to – or, more realistically, which one you’d like to belong to!

What exactly is “Solar Salicylate” (a note used in Squid)?

Salicylates are raw materials naturally present in nature. They give an ethereal and powerful airy effect, ranging from salty to green or floral facets. In Squid, they are massively used to convey the salty effect and carry the formula structure.

How did you design the ink accord? Could you reveal a little bit what goes into that accord?

When you asked me to push the ink accord, I worked with the IFF tool “Scentemotion”, which helps the perfumer determine which raw materials are linked to the colour blue. From my own experience of preparing “nero di sepia” sauce for pasta, it had to smell salty and velvety at the same time. There is a proper density to achieve in the olfactive texture of the ink accord. I used a combination of resins and balsams.

Now that the scent is finished, how do you describe it?

I love how with you we created this new kind of “marine” family, miles away from the typical marine citrusy ozonic accord found in the classics! Squid is a marine amber, fresh and sensual.

Did you surprise yourself with Squid? I was, because when I first learned about the perfumes designed by you, they seemed to be more on the mainstream side. But people who had smelled Squid all told me it was very “niche”. What scents do you enjoy creating more, niche or commercial mainstream?

Working on the American fragrance market, I was asked to focus on the more commercial segments. I rarely worked for niche brands in the past, except for Aesop, Jo Malone, Atkinsons or Diana Vreeland. But I did a lot of artistic collaborations to quench my desire to create edgy fragrances, as I did with D.J. Kid Koala when I did his olfactive opera for the Luminato Festival in Toronto, Canada, or with Robert Wilson on the theme “Voluptuous Panic”. And Serge von Arx, with whom we did two workshops in Norway and in Switzerland on olfactive scenography.

Now I’m working much more on niche brands, and I absolutely love it. Stay tuned!

If you would design any perfume for Zoologist, which animal would you pick?

Aaaaah! I have some in mind with the full olfactive story! One is very, very, edgy! My work on olfactive scenography helps me a lot to give a strong olfactive context linked to the animal. There’s one in particular I would LOVE to execute! It’s about speed.

Thank you so much!

Could you tell us about yourself?

I was born in Brazil, where I graduated in marketing and advertising before moving to France in 1993. In Paris, I did a Master’s in Semiotics, but graduated in with a degree in Cinematography from an art school. After a couple of years working as a set designer for films in France and Brazil, I decided to go for a new challenge in the perfume world.

Have you always been aspired to be a perfumer?

To be honest, I’ve never thought about this profession, even though smells have always been part of my life. You know, in that period, there were fewer perfumers than astronauts in the world. In 2006, at age of 36, I decided to see a coach for a career orientation, and I discovered the perfumer’s world after the many vocational tests she subjected me to. We worked together for three months. In the end, I was preparing my application for ISIPCA, the perfumery school in Versailles. Only 8 persons were accepted that year into the Fine Fragrance course.

Above: ISIPCA, a French school for post-graduate studies in perfume, cosmetics products and food flavor formulation

Above: ISIPCA, a French school for post-graduate studies in perfume, cosmetics products and food flavor formulation

You went to perfumery school 13 years ago. Could you tell us about the program?

The program was entirely based on fine fragrances – six hours a day of studying ingredients and making perfume accords in a lab. We learned the basics of perfumery, studied and memorized ingredient after ingredient, and the main accords and structure of iconic perfumes such as Lily of the Valley and Diorissimo, Shalimar and many others. Then, the evolution of materials, regulations, the modern version of each accord and the perfumes’ structure. But when you study very old perfumes, you can’t get a precise idea of their smell, because you can get only the modern versions. So I started to buy vintage perfumes so I could have the original compositions and gain a deep understanding of each formula. Also, the perfumer’s style, the materials available at the time, and the social and political context of the year of the creation, because the industry was very influenced by that. Vent Vert was created in 1945 by the genius Germaine Cellier just after World War II, when people needed to be reconnected with nature. In this fragrance, you have nature in your face. It’s a very green, floral, impressive masterpiece with a huge amount of galbanum.

Some of my classmates from the ISIPCA class were Isabelle Michaud, whom you already know – she’s a Canadian perfumer and owner of Mon Sillage; Octavian Coifan, a historian and perfumer; Christian Dullberg, who has a perfume company compound in Germany, and a perfumer from Taiwan.

During our perfume training, we had access to the Osmothèque and private classes with Jean Kerleo and other perfumers. We also had access to the library, where we could do research on old books with formulas and other treasures of perfumery.

After graduation, you didn't become a perfumer…

After graduation, I didn’t work as a perfumer for big companies because the perfume industry in France was/is saturated and they don’t take people older than 30. If they did, they would send them to work abroad. Just before applying to ISIPCA, I called Frédéric Malle to get his opinion about the school. He advised me to do it and to go to Asia or Brazil (which are big markets).

Wait – you knew Frédéric Malle back then?

I just picked up the phone and called their office. He answered the phone, and I spoke to him. I'd been to his Rue de Grenelle store before and he was often there.

The other reason I didn't work as a perfumer for a big company was that I wanted to remain independent. In 2007 it wasn’t easy for me to start my own business, so I decided to work for perfume brands in the commercial, export and training areas to get more experience of the market. I started at Natura Brasil, passing by Dior, Chanel, Tom Ford, Nina Ricci, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Serge Lutens, Guerlain, Cartier, and many others until arriving at Frédéric Malle, where I stayed for five years. It was one of the greatest experiences of my career. The environment, the quality of each fragrance, the perfumers, the DNA of the company based on the sophistication of great French traditional perfumery, his experience, and his vision… As the company was very small, I was engaged for exporting and training, evaluating perfume concentrates with him, smelling a new project from beginning to end, and understanding the changes of each test until the final version. Sometimes, what you prefer is not what it has to be in the market.

A perfume or aromachemical company needs more than just perfumers for sure.

A perfume company needs many perfumers on their team, but not only for fine fragrances. It needs a team of perfumers for house products, cosmetics, toiletries, and olfactive marketing. The chance to get a job in fine fragrance compared to other areas is maybe about 5% or less. The volume of production in all the other areas is bigger and more important, even though it’s not as prestigious as fine fragrance. Another career is the evaluator, who is someone between the perfumer and the marketing team, responsible for translating all the concepts for both parts, perfumers and marketing.

Above: Perfumery Class by Daniel Pescio

Above: Perfumery Class by Daniel Pescio

You now hold perfumery classes regularly. Can you tell us more about that?

In 2010, I created my own company and started to build my own lab. I was still working for brands, but when I left Frédéric Malle in 2015 I was able to dedicate myself to develop all my abilities as an independent perfumer. I started creating for independent brands and private customers, being a consultant, teaching and organizing perfume workshops and professional courses for adults and children in France, Brazil, Hungary, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, Austria and UK and all around the world.

I’m a very curious person, and everything related to the sense of smell and taste interests me a lot. Wine, chocolate, teas, incense… all of them are new languages, but linked to each other. Tasting and smelling are completely connected and enrich our perception. At the beginning of learning how to taste or to smell and describe all the sensations, feelings and notes, it is hard. It needs patience, training and perseverance, but quickly you see that you are improving and the world becomes colourful.

Above: Kodo Incense Ceremony

Above: Kodo Incense Ceremony

At the moment, I share my time between teaching and creating, but also with my Kōdō practice and research. Koh-Do (the incense ceremony) appeared during the Momoyama period, known as a period of renaissance in Japan. It is considered one of the geido, or refined arts that are supposed to be performed according to certain rules and manners, like the tea ceremony and ikebana. Among aristocrats and high-ranking samurai, it shares popularity with the tea ceremony. In this respect, Japanese incense, or koh, is somewhat different from perfume in western countries. Later, Kōdō branched off into several schools, of which two leading schools survived: the Oie-ryu School and the Shino-ryu School, where I do my learning.

I have to mention how our perfume collaboration came about! In retrospect, I find it fascinating! A few years ago, through a perfume sell/exchange Facebook group, I bought some fragrances that you owned. When I received the package, I found a sample of your own work. When I smelled it, I thought it was excellent, and had to learn more about it from you! My initial reaction was that your work smelled very "French". It's a very abstract feeling. Could you describe your perfume style?

That’s a fantastic way of meeting and then collaborating, because when I sent you the perfumes with the sample, I never imagined you were the owner of Zoologist. I think at this time you had launched just a few scents of your amazing Zoologist collection. And then you told me you were behind this niche brand.

The sample I sent to you was my first creation after leaving Frédéric Malle. Fleur Cannibale was created in 2015, and the following year I participated in a perfume competition organized by the American Society of Perfumers. One hundred perfumers worldwide participated, with only one constraint: to use a minimum of 2% of Australian sandalwood produced by STF. Accordingly, I decided to take make Fleur Cannibale Santal Extrême, with 8% sandalwood oil in the formula. My creation made the semifinal, with 14 others. Fleur Cannibale is a contrasting fragrance, inspired by abstract flowers and orchids from Amazonia, creamy peach, spices, woods, patchouli, amber, musks, vanilla and frankincense.

About my style … it’s hard to define myself. Some people say they can recognize my style in all my perfumes. What’s is important to me is the quality of all the materials (naturals and synthetics), the balance (I’m obsessed with it) and the evolution of the fragrance, because this is the moment when the perfume will tell you a story.

Let's talk about Chameleon! First, I’ll tell you how I came about this concept of Chameleon as a perfume! I've always been fascinated by the fact that the island of Madagascar has the most species of chameleons in the world. And through a documentary on Chanel No. 5 and baking (yes, baking) I learned about the famous Madagascar ylang and vanilla, which are two important export commodities of Madagascar. When I proposed the concept of Chameleon to you, I insisted that it had to include ylang and vanilla. I also proposed that the perfume have a special quality of “colour changing”, which is probably the most notable characteristic of a chameleon. Have you heard of synesthesia – the ability to “see” colour when you smell certain things? I have always wondered if we could create a perfume that “shifts colour” as it develops on our skin.

Chameleon is an amazing project and was a true challenge for me. First, because I wouldn’t have created this perfume based on an ylang-vanilla scent as a main accord. Otherwise, it would be just one more ylang-vanilla perfume on the market. The challenge was to translate this concept to design a fragrance. Also, I was a bit scared by the fruity facets. My first thought was to produce an accord to give the impression of the scent of skin touched by the sun and the salty breeze by the ocean. I chose some "Ylang Ylang Extra" oil from Madagascar, which was already very fruity, and the fruity facets I worked not only with fruity notes, but also with floral notes having fruity facets. That’s the aim of Chameleon. And then you have other flowers, spices, exotic woods, amber, opoponax, vanilla, patchouli, musks…

It’s interesting to talk about synesthesia. I remember during my first class at ISIPCA. We were learning how to describe a scent, because normally we don’t learn to talk about scents. We don’t have a common vocabulary for it. The teacher said, "You can try to link each scent to a specific colour!” Well, I couldn’t do that, but now I do that with children, and it’s amazing! They can say different colours, but often they say them with the same intensity. The synesthesia process is very much used in my Wine, Chocolate and Tea workshops, because you need to use more than one sense to get a full perception of something. For example, when you take a wine, you have to describe the colour, whether it’s bright or opaque, and then you smell and then you taste. For this experience, you use four of your five senses: the view, the smell, the taste and the touch with our tongue, which has taste buds responsible for the perception of temperature and texture. When you are aware of it, the experience is very rich. You can enjoy every single moment of each sensation provided by your senses.

As we developed the scent, I thought the synesthesia concept might be too difficult to realize. (I don't have synesthesia, and the colours people "see" by smelling are very subjective.) However, you had a different idea of what Chameleon could be, and you persuaded me with your unique vision.

Yes, synesthesia and sense of smell are very personal, very subjective. There is no right or wrong, but only personal or technical way to describe a scent. If you say green for patchouli, I would say you can keep it as a personal reference. But the smell is not considered green to professionals.

The chameleon’s skin is a mirror of nature. That was what I tried to translate into a fragrance. The concept of the skin being the mirror of everything you can have on the island of Madagascar. To make this “skin accord”, I put Ylang Ylang Extra Madagascar oil with a lot of Salicylates and Cashmeran. These makes up almost 40% of the fragrance composition.

I worked very carefully with the vanilla accord, with musks and opoponax. I wouldn’t want to produce the same effect that we have in most ylang perfumes. Another challenge for this project was to give an abstract feeling, despite the presence of a huge amount of ylang in the formula.

People might say that Chameleon is a tropical fruity scent, but I think it is quite different from the typical tropical fruit scents I’ve come across before.

Ylang ylang is one of my favourite flowers. It has proper fruity facets, but it is also animalic, different from the indolic found in flowers such as jasmine, Lily of the Valley or orange blossom. Most of the ylang fragrances are very "Monoi", i.e., a vanilla scent with a huge amount of Hedione. And, in some cases, with woody facets of gaiacwood or very fruity and sugary. So, the moment I got the Chameleon brief, I thought of all these aspects and started thinking what I would translate into this creation. It was the beginning of a trip in my mind through Madagascar, feeling everything I could find on this tropical island. Beaches, sun, heat, ocean breeze, skin scent, sensuality, exotic woods, fruits, spices, and the daily life of the chameleon. My approach was to make the ylang ylang into a musky-skin-salty-sunny accord in the centre of the fragrance, like the solar orbit, with green-acidic exotic fruity facets combined with violet leaves and frangipani. Cashmeran and Salicylates are very important in this accord as the abstract feeling I would give to this fragrance, because of the effects of chameleons in nature. Sometimes it’s obvious they are there, but we can’t really see them.

Another point which is important is the evolution of the fragrance into something smooth, calm, with this musk-vanilla-amber feeling. It reminds me of chameleons losing the reflections of nature and becoming white.

What is next for you?

The most important project for this year is going to be in Japan.

In 2017, I started practicing Kōdō in Japan and France, and last year I decided to make an olfactive project related to this Japanese art and presented it to the Villa Kujoyama’s art project competition. The Villa Kujoyama is a French public institution set in the mountains of Kyoto. It’s a multicultural place of interdisciplinary exchange and aims to strengthen intercultural dialogue between France and Japan. Villa Kujoyama is the equivalent of Villa Medicis in Rome.

My project, "Listening the scents or the Art of the invisible", was the winner in the Fashion and Perfume category. I will be in Japan to do research, present the project and organize some perfume workshops from September to the end of December 2019.

Before that, I will be doing some fragrance creations for independent artists and brands, bespoke perfumes, education and training, consulting for brands and private projects, perfume, wine and chocolate workshops, and organizing my project to launch my perfume brand in 2020.

Wow, that’s wonderful! I can’t wait to smell your own brand of perfumes in the future!

Zoologist Chameleon will be released on March 15th, 2019

Please tell us about yourself!

First off: hello, everyone! Thanks for tuning in! 😀

Other than liking sunset walks on long, sandy beaches (that’s a joke, actually), I’m a bit of a foodie. Quite curious about learning about other cultures. Love tea. Enjoy coffee, though it makes me crazy jittery. Love to cook. Incense junkie. Live in a 220-year-old log cabin in the woods not too far north of Atlanta. I’m an old soul living in a modern world.

This is starting to sound like a dating profile!

Can you tell us more about your perfume company?

Rising Phoenix officially started back in 2011, while I was still in med school in San Diego, although it was 2014 before we really started launching products.

Many that follow my work know that I work in Chinese medicine. I’m in private practice in Atlanta. I spent some time working in three hospitals in Shanghai. In my earlier years I spent my last year in university in Avignon, and worked in Paris after college. I’ve been fortunate to have traveled extensively.

While in med school we had to memorize quite a bit of information about hundreds and hundreds of medical substances, including the Chinese pinyin, the common English names, and the Latin scientific names.

The Latin names started tugging at something in the back of my mind. It didn’t take me long to figure out that pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, cosmetics, fragrance, flavour, and the incense and spice trades were all built on the back of herbs. Herbs I was really diving deep down the rabbit hole on.

In my third year of school, something clicked and I realized, “I could be a physician. Or, I could be a physician, and… !” I wanted to tap into a much larger world that was built on the back of something most never think twice about: herbs. Foundations in a multitude of global modern-day markets.

Since natural oils distilled/extracted from herbs – what we call essential oils, “absolutes”, etc. – are really pharmaceutical-grade herb extracts, fragrance seemed like a natural place to start.

Have you always aspired to become a perfumer?

Ha! No. I have always wanted to help people. That was pretty open-ended.

As a kid, I wanted to be an archeologist. Or a spice trader. (Seriously, I was a weird kid). I worked in film and television before going back to med school.

It wasn’t until years later, when I was working as a physician and focusing on what I call my “golden triangle”– the point of intersection of the medicine, cosmetic/fragrance, and incense trades – that I realized I kinda DID become both an archeologist and a spice trader!

Many don’t realize that, historically, it was physicians and pharmacists that made fragrances. Up until about 100 years ago, if you were going to buy perfume, your local pharmacist was likely making what you were wearing. In the more distant past, fragrance (i.e., perfume and incense) were considered medicine first, as well as something that smelled nice.

Physicians have been behind fragrance since the dawn of fragrant time.

Ever drank a Coca Cola? When I was growing up in Atlanta, many folks know that Coke’s inventor, Pemberton, was a pharmacist. Sodas in the beginning were medical elixirs. What became Coca Cola was originally a treatment for morphine addiction, which was a huge problem in the 1880s, just after the Civil War. Dr. Pemberton was a war vet and an addict.

Who were Johnson & Johnson? Three brothers that sold medical and pharmacy equipment.

Who was Dr. Pepper? The inventor, Charles Alderton, was also a pharmacist in the 1880s. Dr. Pepper was also a medical-elixir-turned-popular-beverage.

Ever used Listerine? Dr. Lister’s work in England in the 1860s inspired Dr. Lawrence in the US to create a surgical antiseptic based on eucalyptus essential oil, menthol (likely distilled camphor at the time or camphor resin), methyl salicylate (better known as white willow bark, now synthesized and used as an over-the-counter painkiller), and thyme essential oil in an alcohol base.

Realizing that a lot of common household name-brand products of today really started from a place that I, myself, somehow found myself working in inspired me to apply my work in medicine to a much broader body of work.

Hence the name: Rising Phoenix. Giving new life to old practices.

So now you juggle between two businesses, acupuncture and perfumery. Do you wish to take your perfumery business to full-time?

In short, yes. It’s been moving that way since I launched. Fortunately, my work all comes from a common root.

I actually was a contributor to a research paper about ambergris, the first of several that will be published.

I am also part of a think-tank company called Botanical Biohacking, a US/Tibet company developing a variety of cutting-edge Chinese medicine pharmaceuticals for the western market.

Fortunately for me, whether I’m “sculpting or painting”, herbs are herbs. Whether I’m making fragrances or treating patients, I am doing the work from a common root. To me, it’s all the same.

To my understanding, your perfumery products at this moment are just attars. Why attars instead of alcohol-based perfumes?

That is mostly true, yes.

I have a larger commercial project that I’m working to put together the capital to launch. Given my unique background, it’s larger than “just fragrance”. I plan to be making some big waves very soon.

I also am involved in distilling some of the key components I’ve become quite well known for, and I’ve also developed some products for some other companies in the Indian and Gulf markets.

But for now, I’m growing my existing line of products organically.

Personally, I prefer naturals to synthetics and cater to a more naturally minded audience. I think naturals really shine in attar form. In alcohol/EdP fragrances, naturals tend to smell a bit flat, sometimes a little murky. But as I make my attars, well, you know. They get nominated for awards. After all, that’s how you and I met.

I’ve become the largest artisan attar maker in the world over the past few years. It seems that, more and more, I run into folks that are into commercial fragrances who are at the very least aware of the work I’m known for in the artisan niche market.

I’ve become quite well known in the artisan sandalwood, oud/agarwood, and incense scene, and currently offer the widest selection of niche aromatic products anywhere on the Internet.

My attars, in addition to my upcoming commercial EdP line, are all a part of my larger plan.

I have observed that there is a rise of attar culture and business in the world of niche/indie perfumes. What can you tell us about your customers and the subculture of attars?

I actually think that a community of artisans that I belong to might at least in part be responsible for that: www.ouddict.com.

Certainly, Amouage’s original attars, especially now that they are no longer making them, have sent folks searching for other attar resources. As have Claire Vukcevic and Kafkaesque, whom both love attars. Their reviews have also brought more attention to the style.

As I mentioned before, I’ve grown to become the largest artisan attar maker, possibly in the world, but at least here in the West. I’m quite well known for my artisan mysore sandalwood oils as well as my artisan oud oils. My attars are big sellers.

I think I’ve played a hand in inspiring many of these other artisans. I know they inspire me. As we are all colleague-competitors, as I call our little community, I’m commonly telling folks that we are stronger together than we are apart. Running a small business is already a practice in isolation. It’s nice to have a collaborative community. These guys are talented, and quite nice folks, as well.

I think our combined work has been helping to bring an old (and still the largest, albeit rather unknown in the West) form of fragrance appreciation to the West – that of attars.

Do you think more people from the Middle East are now wearing spray perfumes rather than attars, but more North Americans are wearing attars?

Yes. In the Gulf markets, “Western fragrances” (i.e. alcohol-based fragrances) are on the rise.

However, wearing pure (natural) oils and concentrated (modern perfumery) attars is still predominantly how much of the Middle and Far East wears their fragrances. This in large part has to do with the large Muslim population in the Gulf and SE Asia, and their tendency to avoid alcohol, even in fragrance form. And, particularly in the Far East, they still have a tendency to like lighter, more natural compositions.

Here in the West, I think there is a growing awareness and appreciation of older forms of perfumery. Alcohol-based perfumery is really French or British-style perfumery. It is not the only form of perfumery, and far from the oldest form.

I don’t want to make any ridiculous claims, but I do think the growing popularity and visibility of my work and that of my colleagues over the past few years has contributed to this growing awareness. Certainly, the artisans of the Ouddict Community are making this rather unknown form of perfumery much more visible in the West.

I’m thinking Dodo might need to be Zoologist’s inaugural attar!

I remember seeing your Facebook photos of oud/agarwood you have acquired from various sources. Can you tell us more about them?

According to the Internet (reliable, right?), ebony is the most expensive wood on the planet. In reality, agarwood is the most expensive. Sandalwood is the second most expensive. Agarwood usually refers to the wood, and oud often refers to the distilled oil obtained from agarwood. It is a regulated material, and I am licensed to both import and export it.

The root of “perfume” is Latin – “per fumum”. Meaning, “through smoke”. In many cultures today, the term “perfume” refers to BOTH incense and what you and I would call perfume or fragrance.

The backbone of both the fragrance and the incense industries is agarwood and sandalwood. Only recently is the West being reintroduced to agarwood, although it has long had a history in Europe and the Catholic church. King Louis XIV of France was known to wash his clothes with and douse his bed in oud hydrosol, for example. The Catholic church has been using agarwood in incense since the inception of the church, and Jews and Muslims alike have made use of “precious aloes” (i.e., aloeswood, a.k.a. agarwood) since their respective beginnings, as well. In the East, it has been well-known and used as both fragrance and medicine dating back long before the written word. Agarwood has close to 10,000 years of recorded trade. It is, by every definition of the term, one of the original global trade commodities.

Rising Phoenix is the premier resource for high-quality agarwood in the US and in the West at large. I definitely offer the most diverse selection of species and origins, as well as a wide diversity of forms through which to enjoy it. Agarwood, as it happens, has a terroir diversity similar to that found more commonly in tea, coffee, chocolate, wine, scotch and whiskey.

Agarwood has captivated the minds of people for millennia for a reason. See, a rose smells like a rose smells like a rose. Certainly, country of origin, species of rose, and extraction method play a role in how a rose oil will smell. But they will all smell of rose. Not too much diversity. Line up 10 different Oud oils and many may guess incorrectly that they aren’t all Oud. Depending on the origin, species, and the vast array of creativity used in distilling it, the oils have an almost limitless number of iterations in how it might smell.

Same can be said of the wood. There are many cultural differences in how it is used. In general, the Arabic tradition is to burn on coal. The Japanese (and as an extension, Chinese and Taiwanese and Asians in general) heat with an indirect heat source (like a coal buried in ash) or, more commonly today, on an electric heater with more gentle heat. Combustion vs. volatilization. There is also the method of “senkoh”, that of the incense stick without a wood core that’s most common in the Japanese tradition. Not to mention, it is used in Bakhoor (Arabic) and the wide range of Asian compounding traditions of incense using agarwood (and sandalwood) as the backbones upon which to build a blend.

The fascinating thing about this wood is the sheer diversity of ways to use and enjoy it, and the resulting vast array of how it may smell. One could spend a lifetime studying agarwood and oud and never exhaust discovering some new scent found within it.

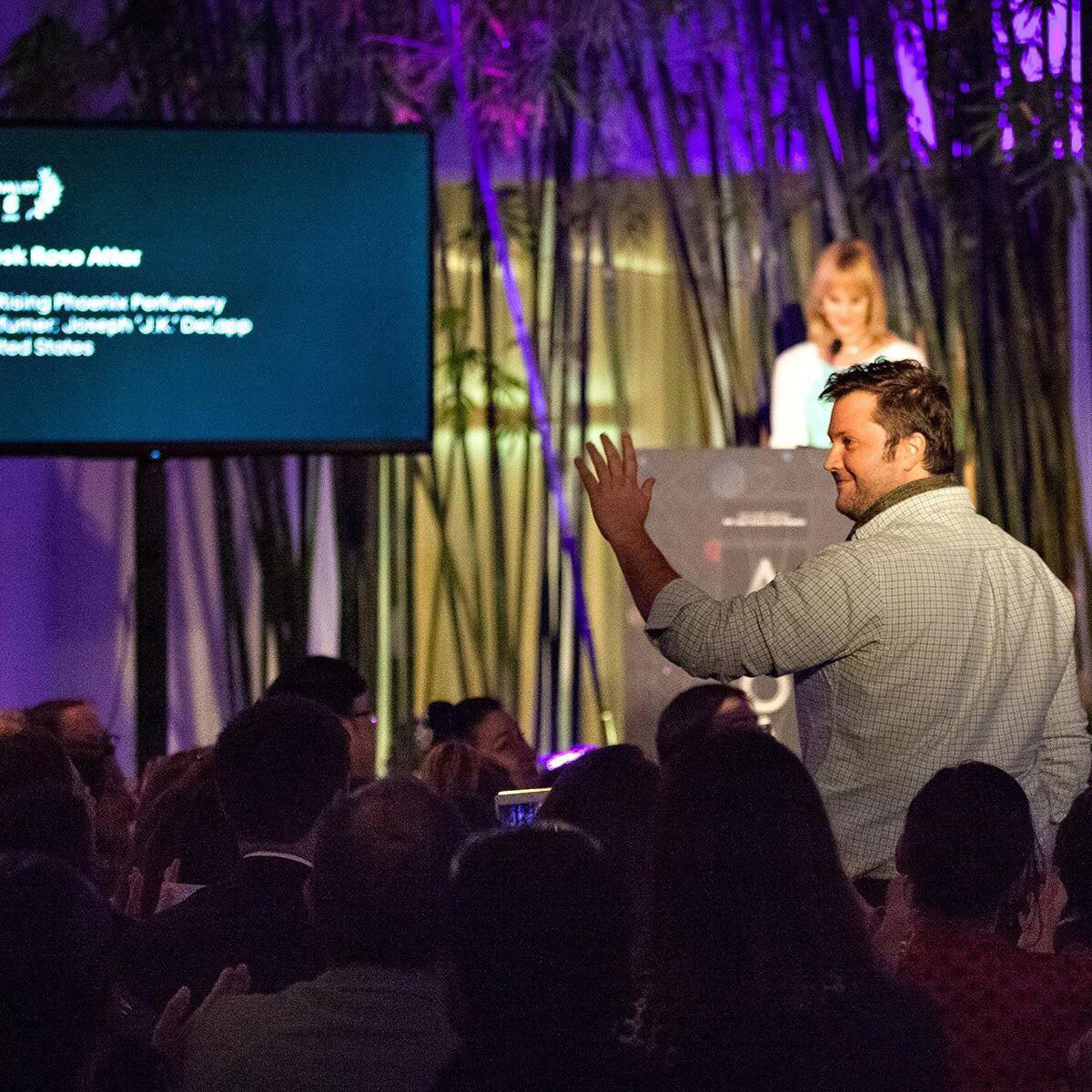

In 2017, you started a Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign to bring your business to a higher level. How did it go? What is your ambition?

The campaign itself wasn’t successful enough to raise the capital to launch what I’ve got planned. However, it’s continued to be useful, as I am actively working on raising the capital for my commercial launch.

I spoke earlier in the interview about my larger ambitions, and folks should know that I never stopped fundraising. I am getting quite close to having the capital to actualize what I’ve been working on these past years.

For the time being, I’ve been growing organically. The publicity from Dodo and my work with Zoologist will also serve as key signposts to the good work I’ve been doing and the growing success of Rising Phoenix as a brand. In other words, stay tuned!

In retrospect, did you think you were too ambitious, compared to much smaller startups that grew their business “organically”?

“Shoot for the stars and you might hit the moon”, right?

Ambitious, yes.

I shot a pilot almost 15 years ago for the Food Network as the host of a “Field to Fork” kinda food show with one of Martha Stewart’s former producers. The show didn’t get picked up, but have you seen Netflix food shows lately? I was also contracted a few years back for a show about ambergris being developed for The Discovery Channel. That also didn’t get green-lit. We’ve seen more and more documentaries, and even a show called “Perfume” on Netflix now. I’ve been making attars for years. Attars are now beginning to gain some mainstream appeal in the West. I’ve had a tendency my entire life to be ahead of the curve.

I am also a believer in Divine Timing. Things didn’t quite work out when I was hoping, but things are certainly building up to it. I have had a lot of opportunities thrown at me that I haven’t yet been able to capitalize on. But the time is coming. Of this I am certain.